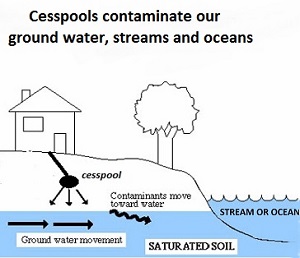

With Governor David Ige’s signing of Act 120 in June, the state Department of Health edged closer to tackling the public health threat posed by the tens of thousands of cesspools scattered throughout the islands that discharge an estimated 50 million gallons a day of raw sewage into the ground. Act 120 allows owners of eligible cesspools to claim up to $10,000 in tax credits for costs associated with upgrading to a septic or aerobic treatment system or with connecting to a sewer system. (To qualify, a cesspool must be near drinking water wells or within 200 feet of the shoreline, streams or wetlands, or it must be connected to multiple residential dwellings.)

With Governor David Ige’s signing of Act 120 in June, the state Department of Health edged closer to tackling the public health threat posed by the tens of thousands of cesspools scattered throughout the islands that discharge an estimated 50 million gallons a day of raw sewage into the ground. Act 120 allows owners of eligible cesspools to claim up to $10,000 in tax credits for costs associated with upgrading to a septic or aerobic treatment system or with connecting to a sewer system. (To qualify, a cesspool must be near drinking water wells or within 200 feet of the shoreline, streams or wetlands, or it must be connected to multiple residential dwellings.)

But Act 120 has its limitations, according to Robert Whittier of the DOH’s Safe Drinking Water Branch. The act caps the tax credits in a given year to $5 million and they expire in five years.

With upgrades to individual cesspools likely to cost about $25,000 to $30,000, the $25 million in total credits allowed by the act will likely cover only about 2,500 of the 6,900 qualified cesspools that the DOH has identified, he said last month at a lecture at the University of Hawaii at Manoa.

What’s more, concerns remain over whether the credits are best applied to cesspools within 200 feet of coastal or surface waters and whether converting a cesspool to a septic system —which would require a leach field—would offer any improvement in areas with porous, rocky soil.

Whittier pointed out that if a single person in a remote area had a cesspool within 200 feet of the coast, upgrading it probably wouldn’t be as valuable as converting cesspools in an area like Waialua, Oahu, where there is a large cluster of them, albeit half a mile from shore.

By converting those in Waialua, “you’re going to get a bigger bang for your buck,” he said.

He added that there are ongoing discussions about how to best implement Act 120 and that the DOH has identified high-risk areas that need to be focused on.

According to statements by Dr. Roger Babcock, a civil engineering professor at UH who attended Whittier’s talk, in addition to focusing on high-risk areas, the department may also need to provide guidance on what kind of upgrades should occur and where.

A septic system pumps waste from a holding tank onto a leach field, where the waste is spread out and filtered in the soil. But that type of system is fairly limited in areas with a high concentration of similar systems and soils that don’t allow the dispersal field to do its work, he said.

“There may be no improvement especially if you have a high density [of onsite disposal systems]. Like on the Big Island, where you have very poor soils and you essentially have just [waste] injection [into the ground], septic is not going to help at all,” he said, adding that people there would be better off installing an aerobic treatment plant, which doesn’t necessarily cost more than a septic system.

Hawaii island has by far the most cesspools of any other island. And in places such as East Hawaii’s Hawaiian Paradise Park (HPP), with more than 4,000 cesspools and “absolutely no soil,” according to Whittier, aerobic systems may be the only way to prevent the continued contamination of the subdivision’s drinking water wells.

HPP, which is not served by the county water system, has about 250 potable wells and is home to about 4,500 residents. Last year, the University of Hawaii and the DOH sampled 32 of those wells and found that half of them tested positive for total coliform and a quarter of them tested positive for E. coli bacteria, which indicates contamination by sewage.

The incidence of bacteria detection increased near the coast and after a heavy rain, Whittier said. He also stressed that researchers did not test for longer-lived viruses. (More than 100 types of viruses have been detected in human fecal matter.)

Given the results, Whittier said the DOH strongly urged HPP residents to use ultraviolet light disinfection systems to treat their drinking water.

More recent studies by the University of Hawaii are revealing additional areas that would likely benefit from a large-scale cesspool upgrade. For example, along Oahu’s South Shore, UH researchers Henrieta Dulai and Christina Richardson have sampled the coastal waters off Black Point, which has never been connected to the Honolulu sewer system, and Wailupe Peninsula and Kawaikui Beach Park, which have.

In the Black Point samples, they found elevated levels of total nitrogen, total phosphorous, and a nitrogen isotope (delta 15N) that has been found to be a good tracer of sewage pollution.

And modeling by the university estimates that the coastal waters off West Hawaii have five to ten times the amount of sewage-related nitrogen than is found in East Hawaii. UH researchers predicted higher levels of nitrogen in West Hawaii because East Hawaii gets much more rain and, therefore, more dilution of its leached wastewater, Whittier said, adding that a separate study of actual delta 15N levels in West Hawaii seemed to validate the model’s predictions of where the coastal influence of onsite sewage disposal system-related nitrogen would occur.

“We want to start replacing existing cesspools in critical areas,” Whittier said. Kahaluu, Oahu, is an obvious place to start. Last year, the area received a lot of media attention when a bather got a serious skin infection after wading in a lagoon there and subsequent tests by the DOH found bacteria levels that were the equivalent to those found in the Ala Wai canal after one of the islands most massive raw sewage spills.

In the Kahaluu case, not only did the DOH find a measurable impact of disposal systems on surface waters, it also verified an adverse health impact, Whittier said.

So what else is being done to address the problem?

Whittier said the DOH is also in the midst of revising its wastewater regulations to prohibit new cesspools.

Last year, then-Gov. Neil Abercrombie chose not to sign administrative rules for the DOH that would have banned new cesspools and phased out old ones, and a House Bill aimed at doing the same died this past legislative session.

Unfazed, the DOH held public hearings in August on rules that would not only ban new cesspools, but also provide the framework for the tax credit program authorized by Act 120. The department’s website states that the rules are expected to be approved by the end of the year, before the tax credit program is set to start. But according to one Wastewater Branch staffer, the division has no idea when the rules will be ready for the governor to sign.

— Teresa Dawson

Volume 26, Number 4 October 2015

Leave a Reply