Is the sighting of one monk seal three years after the acceptance of the Kalo`i Gulch Drainage Improvements’ final environmental impact statement (FEIS) enough “new evidence” to require a supplemental one? How about a monk seal sighting plus the release of unpublished data on the chemical composition and volume of stormwater flows at Oneula Beach Park, through which the improvements would funnel storm runoff?

Those are questions the state Board of Land and Natural Resources will have to decide in the remanded contested case hearing over the Conservation District Use Permit it granted for the project in 2012.

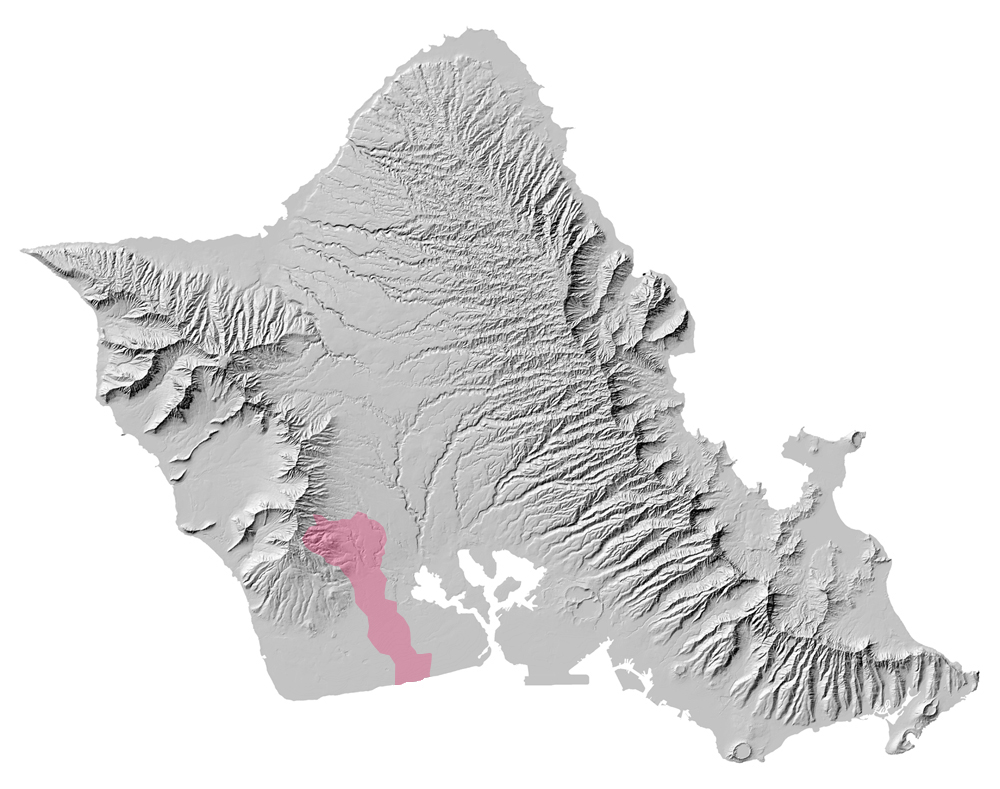

The project —initiated by Haseko (Ewa), Inc., and joined by the University of Hawai`i, the City and County of Honolulu, and the state Department of Hawaiian Home Lands —proposes to lower a 500-foot stretch of a sand berm at the beach by two to four feet while raising the banks higher to direct flows. Creating a stormwater outfall at the beach would free the entities from city restrictions that prevent them from developing portions of their properties in the Kalo`i watershed that serve as retention or detention basins.

Teacher and native Hawaiian cultural practitioner Henry Chang Wo has long opposed the diversion of runoff from urban development into the marine environment where he collects limu, or seaweed.

Represented by the Native Hawaiian Legal Corporation (NHLC), Chang Wo lost his fight against the CDUP in a contested case hearing before the Land Board, but has appealed to the 1st Circuit Court. The judge in that case remanded to the Land Board the issue of whether or not a supplemental EIS is required. On March 13, the Land Board heard oral arguments on the matter.

NHLC attorney David Kimo Frankel argued that data revealed in a 2008 contested case hearing on an earlier CDUP showed that contaminant levels in stormwater samples collected from the marine waters off Kalo`i Gulch are far higher than originally thought. (In 2008, the Land Board held a contested case hearing on a CDUP for the same drainage project, which Haseko had proposed for its Ocean Pointe residential/marina development. The EIS for the drainage project was done in 2005. The board ultimately denied the permit, finding that the project lacked justification. Haseko later brought on the current parties as co-applicants to the CDUP granted in 2012.)

“This data alone raises substantial questions,”Frankel said.

He pointed out that it wasn’t until 2013, as part of the contested case for the new CDUP, that Haseko calculated the volume of runoff to be funneled through Oneula Beach. He also noted that the contested case uncovered previously unreleased data on pollutant concentrations in waters within 100 meters of the beach. The FEIS had only described pollutant concentrations in waters 300 meters offshore.

The 100-meter concentrations are an order of magnitude higher than those that were included in the FEIS, Frankel said.

Finally, Frankel noted that an endangered Hawaiian monk seal was seen during a 2008 site visit, yet the 2005 EIS claimed that monk seals had not been observed in the area.

Given all this, a supplemental EIS would provide critical information to the state Department of Health, the Department of Land and Natural Resources’Division of Aquatic Resources, as well as the Land Board, Frankel argued.

Under the state’s administrative rules, a supplemental EIS is warranted when “the intensity of environmental impacts will be increased, when the mitigating measures originally planned are not to be implemented, or where new circumstances or evidence have brought to light different or likely increased environmental impacts not previously dealt with.”

A Rebuttal

Attorney Yvonne Izu, representing the CDUP applicants, joked that Frankel had planted the monk seal spotted in 2008. That seal, she contended, was the only new evidence to surface after the 2005 EIS that had not been previously discussed or considered during the EIS or contested case hearing processes.

First, she noted that Chang Wo had commented on the EIS, but had not challenged it.

That stormwater constituents exceed acceptable levels is not only something everyone knew, it is insignificant given that pollutants quickly dissipate with the area’s significant wave action, she added.

She also stated that the “new”data on the volume of storm runoff was based on a discharge rate that was included in the 2005 EIS.

“So, is this new information? No, it’s not. It was there,”she said.

The same went for the 100-meter pollutant concentrations, Izu argued, stating that that data came out of modeling done for the 2005 EIS. Haseko’s consultant at the time had modeled pollutant concentrations all along the nearshore area but had only included the 300-meter grid in his narrative report included in the EIS.

Nobody asked to see the data for the 100-meter grid, she said.

“The only thing I admit is new information is the monk seal,”she said. But this is not like the recent Turtle Bay Resort case where an SEIS was required, in part, because monk seals were found in the area and the decades-old EIS for the resort’s development had not even mentioned monk seals, she added.

In that case, more than 50 monk seals were later documented using the beach and it had become a known birthing area. “Here, we saw one monk seal. … The question becomes: is the sighting of one monk seal sufficient to require a supplemental EIS? No, it is not,” she said.

She argued that the Land Board knew about the monk seal and the pollutant levels in the 2013 contested case hearing on the CDUP and decided that they weren’t significant. The Land Board ultimately granted the CDUP, again, on June 13, 2014.

‘Procedural Bootstrapping’

The issue of seizing on information presented during the course of a contested case as new evidence warranting an SEIS seemed to worry both Deputy Attorney General William Wynhoff and Land Board member Chris Yuen.

After hearing Frankel’s arguments, Wynhoff said that new evidence is always going to be presented in the course of a contested case hearing.

“Does ‘new evidence’mean anytime something new comes up?”he asked.

Frankel said he was willing to concede that not all new evidence is important enough to warrant an SEIS. But the evidence in this case was “shocking,”he said, addingthat the presence of the monk seal could be either new evidence or a change in circumstances.

Still, Yuen expressed the same concern as Wynohff. In the 2008 contested case hearing, Haseko consultant Steve Dollar presented the results of his water sampling, which Frankel now says should be considered new evidence that would require an SEIS. Yuen asked whether it would matter if the opponents, rather than the permit applicants, had provided the new information. And if it didn’t matter, would that lead to “procedural bootstrapping.”

“If I take your argument, opponents [in a contested case hearing] could produce information that could require an SEIS,”Yuen told Frankel.

“This discourages an applicant from bringing information that they think helps their case. I’m concerned about this continuous looping,”Yuen said.

Frankel tried to allay Yuen’s concerns, arguing that an SEIS would not be required if the new information didn’t significantly change things.

“I don’t think your decision …will open up a Pandora’s box, a parade of horribles, whatever you want to call it,”Frankel said.

Should the Land Board decide an SEIS was required, Frankel argued, the CDUP would be void.

— Teresa Dawson

(For more on this, see our May and October 2012 and October 2014 Board Talk columns.)

Leave a Reply